WHAT HAPPENS TO those doing routine work when ChatGPT can create a marketing proposal in seconds, and robots can weld car parts faster than any human?

For over a century, such jobs were the backbone of industrial economics. Clerks who processed forms, accountants who bal-anced ledgers and factory operators who assembled identical parts formed the stable middle layer of the workforce. Today, these jobs are under threat. Artificial intelligence (AI) and automation are quietly rewriting the rules of the economy. Machines are no longer confined to lifting heavy steel or sorting boxes; they read contracts, approve loans and manage payrolls.

Automation is not new, but now, it is different. The previous wave consisting of mechanisations and industrial robotics replaced muscle power. The current one replaces mental repetition.

THE SLOW DISAPPEARANCE OF ROUTINE

Economists David Autor and Frank Levy defined routine jobs as tasks that follow explicit, rule-based instructions. In the 80s and 90s, this category dominated global employment from factory floors to office cubicles. It was efficient, scalable and trainable.

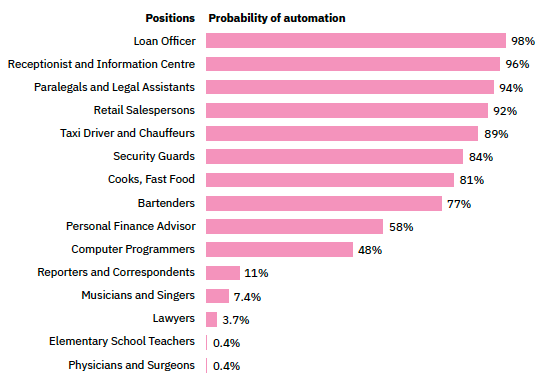

Then came algorithms. Computers recognise patterns and analyse data. Occupations most at risk are those built on repet-itive or standardised tasks—loan officers (98% risk), receptionists (96%), paralegals (94%) and retail salespersons (92%) (see Figure 1).

According to McKinsey Global Institute (2017), nearly 30% of tasks across 60% of occupations can be automated using existing technologies. The International Labour Organisation (ILO, 2024) found that AI poses a high threat to the ASEAN job market, poten-tially replacing 57% of positions. The impact is forecasted to be most severe in manufacturing and routine roles like clerical and administrative work.

FIGURE 1: SELECT OCCUPATIONS RANKED ACCORDING TO THEIR PROFITABILITY OF BECOMING AUTOMATABLE

Source: Bloomberg (2024)

HOLLOWING OUT THE MIDDLE

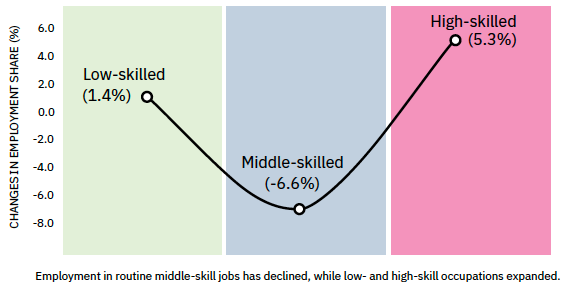

The effect is subtle, but profound. Automation does not create mass unemployment overnight; instead, it reshapes the structure of employment. As shown in Figure 2, methodical middle-skill occupations have steadily declined, while both high-skill and low-skill jobs have expanded—a pattern known as job polarisation.

At the top of the curve, high-skill, high-income jobs that depend on creativity, problem-solving and analytical reasoning are growing rapidly. On the other end, low-skill service jobs such as cleaning, caregiving and delivery remain resilient because they require a human physical presence.

This trend, first observed in the US and Europe, is now accelerating across Asia’s middle-income economies. In Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam, manufacturing once relied on semi-automated assembly lines and clerical support. Now, as AI-powered machines and enterprise software improve, these economies risk losing their comparative advantage in “routine intensive” production. The World Bank (2023) projects that middle-income economies could lose up to 16% of routine employment by 2030, while the World Economic Forum’s 2024 Future of Jobs Report expects administrative roles to decline by 26% in the next five years.

FIGURE 2: CHANGE IN EMPLOYMENT SHARE BY SKILL

GROUP BETWEEN 2001 AND 2022

Source: Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM)

PRODUCTIVITY PARADOX: GROWTH WITHOUT SHARED GAINS

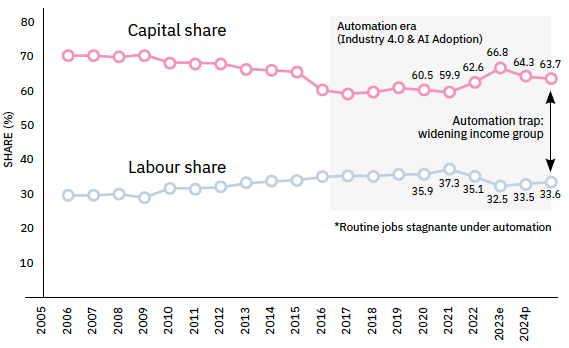

For decades, technological progress meant benefit to the masses. Higher productivity meant higher wages. Unfortunately, this relationship has weakened. Since the mid-2010s, as Malaysia embraced Industry 4.0, the payoff has become more polarised: labour’s share of income has stagnated while capital shares have risen. The same output that once required 10 clerks can now be produced by a single employee aided by software. The International Monetary Fund (IMF, 2024) reports that labour’s share of global income has fallen from 54% in 2000 to 48% in 2022, while capital’s share such as profits, dividends and rents continues to rise.

This “productivity paradox” is visible even in advanced economies such as the US, Japan and South Korea, where productivity has surged over the past decade, but median wages remain flat. For developing economies like Malaysia, however, the risk is more structural—exhibiting the so-called “automation trap”, where technology adoption boosts national output, but traps workers in stagnant or low-value roles.

FIGURE 3: LABOUR VS. CAPITAL SHARE OF INCOME (2005-2024)

Source: Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM)

WINNERS AND LOSERS IN THE AUTOMATION RACE

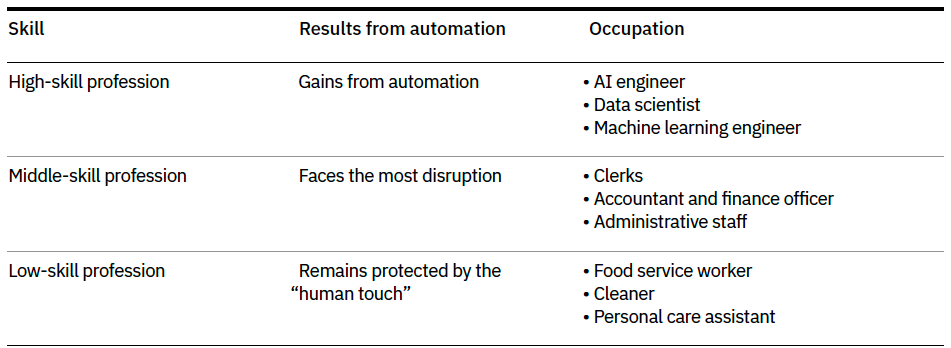

Automation does not affect everyone equally; instead, its impact creates a clear labour market division.

The danger here is not technological progress itself, but the concentration of its rewards. Large firms that possess the resources to invest heavily in AI and advanced automation gain a more powerful edge in the market. Conversely, smaller enterprises, particularly micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) often struggle to adopt automation efficiently. They lack the necessary capital, technical expertise and scale; this results in a widening of productivity gaps across industries. Automation, therefore, risks reinforcing what economists call the Matthew Effect: “To those who have, more will be given.”

Unless addressed through deliberate policy intervention, this effect could hollow out not just the middle class, but the social stability and equitable growth that a strong middle class provides.

THE POLICY GAP

Governments and educational institutions often lag behind technological change, creating a critical policy gap. Many school systems still train students for disappearing clerical or manufacturing roles. To change this, an immediate approach to reskill and adapt must be done. This requires a multi-pronged approach:

ENCOURAGE LIFELONG LEARNING

Prioritise cross-domain skills, critical thinking and creativity, making learning continuous.

INCENTIVISE RETRAINING

Create incentives for firms to retrain, not just replace, workers with technology.

STRENGTHEN SAFETY NETS

Build robust social security and transitional support for displaced employees.

BOOST EQUITABLE EDUCATION

Strengthen the system to ensure its benefits, especially digital skills, reach all citizens, including the economically vulnerable.

SEVERAL ECONOMIES IN ASIA OFFER BLUEPRINTS

Singapore’s SkillsFuture provides every citizen with credits for continuous learning, while South Korea’s Lifelong Learning Account links retraining directly to industrial needs. Malaysia’s TVET modernisation and HRD Corp programmes are steps in this direction, but their scale and execution remain challenges due to issues like fragmented governance and funding inad-equacies.

The key, economists argue, is not to slow automation, but fundamentally to humanise it, ensuring its rewards are broadly shared.

REIMAGINING THE HUMAN ADVANTAGE

Even in the age of machines, some jobs remain uniquely human. Being a doctor, teacher, social worker, designer or an entrepreneur require empathy, nuanced judgment, radical creativity and moral reasoning—what economists call non-routine cognitive work. Their value lies in navigating complexity, building trust and generating novel solutions that require an understanding of human context.

Automation is forcing a philosophical reset in the labour market. While “work” historically meant performing routine tasks for pay, the future requires societies to compete with AI on meaning, not speed.