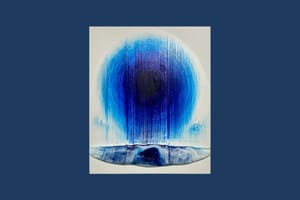

IN HER EXHIBITION Tomoe, Mina Katsuki lets the layers of her paintings sit in plain sight. Thin coats of Egyptian blue are laid down one after another, finished in a deliberate sweep. Small ridges form where pigment has gathered along the stroke’s edge. The works don’t hinge on metaphor—they stay with the mechanics of their painting: the pressure of a wrist, the drag of pigment across canvas. This is keshiki in practice—not an idea, but the residues of decisions made in real time.

The Japanese aesthetic of keshiki—“scenery”—is experienced by Katsuki during a mountain hike. She had bypassed a famed landmark, and had stopped at a tree most hikers would barely register—its bark thick with wet moss, its limbs bent outward in sharp, uneven angles; the kind produced by years of snow load. Those crooked branches reminded her of brushstrokes pushed to their limit. That brief moment on the mountain was not just inspiration, but keshiki in practice: an encounter with form shaped by weather, accident and time.

Keshiki makes the process visible: the stray drip, the shifted stroke, the smudge on ceramic. Such marks show a work coming into being, shaped by both control and chance. This approach links Katsuki to a broader lineage, in which meaning arises from action rather than representation. From Sengai Gibon’s ink dispersals to the performative experiments of Gutai, artists have long treated the mark as a record of the body at work. Murakami’s paper-tearing and Kazuo Shiraga’s body-driven painting push this further, turning process into form. Tomoe continues this trajectory, translating those principles into contemporary abstraction.